By Bethany L. Hawkins, Chief of Operations, AASLH

One common criticism of historic house museums is they are static and impersonal. Even when curators and interpreters try to make the house look “lived in,” it often fails to invoke the feeling of home for their visitors. I believe we have constrained ourselves for years with our mission statements and collection policies freezing our historic houses in time and, as a result, constructing a barrier between our visitors and the connection to place.

How can we expand our focus to help visitors better understand the practice of history through the stories we tell and the artifacts we display in our historic house museums?

As a former historic house museum director, I understand the issues with deciding how to interpret a site. For decades, the house I managed was frozen in time from the time of the house’s final renovation in the 1850s to November 27, 1863, when the person on whom our narrative focused died. I made it my mission to expand that narrative from a single person to the fifteen or so white people who lived in the house over time and the fifty-two people they enslaved. But our collections policy restrained me, as we had few items in our collection that went past 1863 and no information about the enslaved population. To make my vision a reality, several things needed to change, including our mission and artifact collection.

Over my seven years as executive director, I was able to research the white members of the family to create a more complete (and not always flattering) picture of their life between the end of the Civil War to when the family sold the home to the State of Tennessee as a museum in 1930. I also researched some of the enslaved people on the farm. We incorporated their stories using primary source documents in a new museum built on the historic site. The museum included two galleries with the purpose to move the story of the inhabitants of the plantation from 1863 through reconstruction and the birth of the Lost Cause movement to the beginning of the Great Depression. It did require educating our board to change our mission statement and collections policy. This was not an easy task as there were some descendants on the board and a lot of the history I proposed sharing was not flattering to their family. The board did agree to make the change, and I am pleased to say the site continues to share this broader narrative with visitors, particularly in the museum building.

While I was there, however, we did not change the look or the interpretation of the historic house much past its central Civil War story. It remained a snapshot of a very small time in the home’s 212-year history. Since I started at AASLH in 2006, I have visited many historic house museums across the country. The vast majority, like the one I managed, are stuck in their “period of relevance” as stated in their National Register of Historic Places application or other official historical designation. I recently visited a site committed to changing this pattern.

For years, I have worked as a volunteer consultant with Oaklands Mansion in the town where I now live. I have watched them struggle with visitation numbers, identity crises, and political turmoil with the city government. I also watched them slowly evolve from a one-narrative site to one that I personally believe could be a model for other historic house museums.

For years, I have worked as a volunteer consultant with Oaklands Mansion in the town where I now live. I have watched them struggle with visitation numbers, identity crises, and political turmoil with the city government. I also watched them slowly evolve from a one-narrative site to one that I personally believe could be a model for other historic house museums.

For decades, Oaklands was also the victim of the one-narrative story and, being in Middle Tennessee, it revolved around the Civil War (just like a dozen other historic sites in the area). In the last five years or so, the staff thought about how they could expand their story but were primarily focused on decorative arts. This added to the static feeling in the house. I was in and out (not on regular tours) and there was always the same settee, china, silver, and quilts trapping the house in the 1860s.

Prior to the pandemic, I noticed things starting to change. A public history class from Middle Tennessee State University (only a couple of miles from the site) created the first exhibit for Oaklands about their enslaved people. Later, a student from MTSU who worked for Oaklands part-time researched specific enslaved people and created biographies for an online exhibit that focused on their lives post-slavery. This led to a partnership with the African American Heritage Society of Rutherford County, and they are now building a monument to the enslaved people from Oaklands buried in unmarked graves in nearby Evergreen Cemetery.

But, when I visited the site in January 2022, I noticed a monumental change in the historic house. It no longer stopped at the Civil War. The curator and other staff added photos, artifacts, and stories that showcased the long history of the house itself. They added a Murano glass chandelier in the upstairs hallway, recently donated by a family member of one of the last families to live in the house in the 1920s and 1930s. Other artifacts also are scattered about the house, adding to the story of the house as a home for many generations.

Most striking to me were the photographs used throughout the house. The staff sprinkled photos of the people who lived in the home from the 1870s to the early 1950s throughout the rooms of the house. They are subtle and among Victorian era furnishings, but for me they made the house feel like a home instead of a static museum. I was surprised about how the whole feeling of the house changed due to these photos and added artifacts. It was no longer frozen in time and hamstrung by a single narrative.

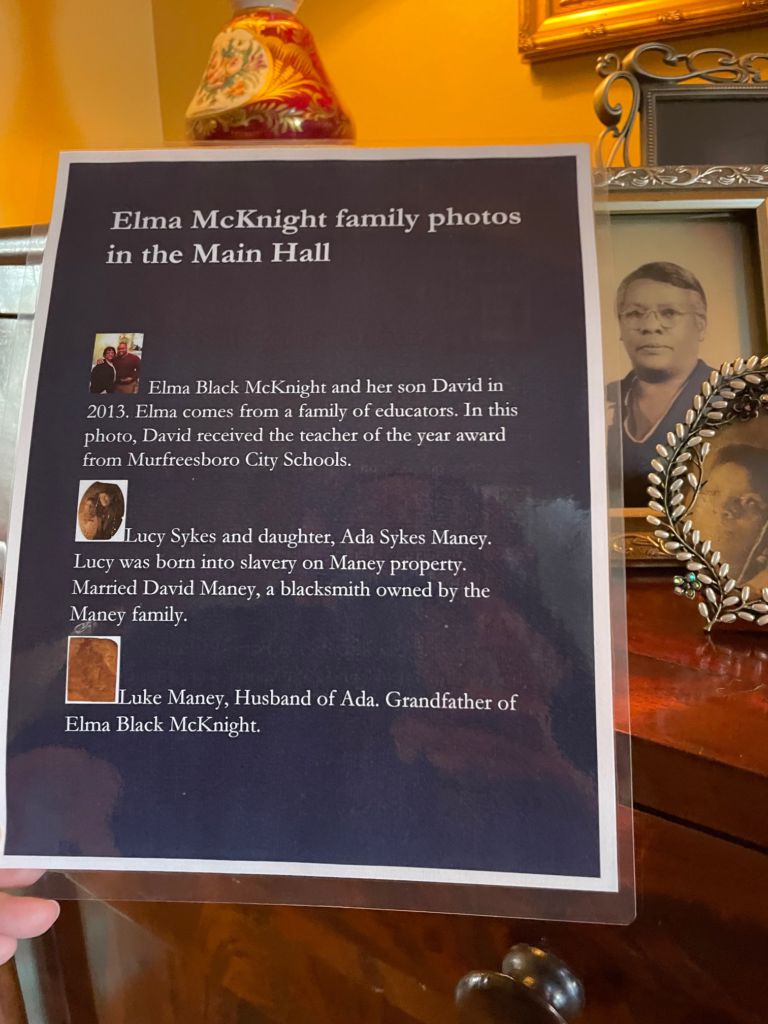

Most affecting for me was a simple display in the main foyer of the house. On a table beside the stairs, they have a series of framed photos of the descendants of the Maney family, the home’s original owners, including nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first century images. There was a printed guide next to the table providing brief biographies of the people pictured.

Across from the stairs on a large buffet was a matching exhibit of descendants of a family enslaved by the Maneys. It also included images from the late nineteenth century to present day along with the biography reference sheet. The center of the display featured a recent photo of a mother and son from the current generations of the family, both teachers in Murfreesboro City Schools, on the day the son won Teacher of the Year from the district. The biographical sketches of the family illustrated the struggle faced after the war for African Americans and connected it to the present day.

These were simple, inexpensive exhibits. All they required were prints of the photos and frames that could have been purchased at a local thrift store. The biography sheets were printed two-sided and laminated. But they told a powerful story. The white and Black families who lived on the ground where visitors walk both called it home, but with very different perspectives. They also both exist today. They have over a century of stories of hardship, sorrow, and triumph because of the time they spent on the land where Oaklands Mansion, its connected city park, and the modern homes nearby currently occupy space. They also remind visitors that the past is not as far away as we like to think. We all came from somewhere, shaped by the stories of our ancestors.

In conclusion, here are five things I think other historic house museums can learn from these two examples:

1. Keep researching. Don’t become complacent about the history you tell. Always make time for historical research on the people, all the people, who once called your site home. Historians all know a hidden gem could be located in the next archival folder.

2. Don’t be afraid to mix time periods in your collections. Look around your own home. Do you only have items from the twenty-first century? Since you are part of the history enterprise, I will guess no. I have decades of old family photos, my mom’s iron skillet, and quilts from my grandmothers. The people who lived in your historic house would have been the same way.

3. Help visitors create a connection to the past. The photos at Oaklands serve as a subtle timeline about the history of the plantation as well as the history of Middle Tennessee. Visitors can use these as visual clues to say that four or five generations is really not so long ago.

4. Include everyone in the story. Post-pandemic, Oaklands switched to self-guided tours with short descriptions of the rooms displayed in each. Each room also includes a story of an enslaved worker who would have spent time in that space. Staff also included some sketches of people, Black and white, who lived in the home or on the property post-slavery, adding to the full narrative of the property.

5. Don’t be afraid to talk about the hard stuff in the parlor. Often historic house museum staff and volunteers want visitors to see all the pretty things they have saved and appreciate the effort it took to save these homes. That is okay, but it whitewashes the experiences of the people who lived and worked in the structure, especially in the South. Try tackling some hard history right off the bat. For example, the Maney family was one of the largest enslavers in Rutherford County with two additional plantations in Mississippi. That is how they could afford the beautiful brick home and fine parlor furniture. Help your visitors make connections between what they see and the true story of how it got there.

Fair warning, some of this will require some soul searching by your board. They may have to expand the mission statement and rethink the collections policy. You may have to educate them on why this work is important. But the result is worth it. During the hour or so I spent in Oaklands Mansion a few weeks ago, for the first time in decades I felt I was in a home and not just a museum. Now, I can’t wait to go back and learn more.