By Bethany Hawkins, AASLH COO

Like many of my colleagues in the history field, I chose to be a public historian because I love getting to connect others to the past and help them understand the present. I also chose it because I hate math and my undergraduate degree only required one math class. One thing I especially hated about math class is when the teacher required me to show my work. It made the assignment take twice as long and was tedious. But it allowed my teacher to see how I reached my conclusion and if I followed the correct steps along the way.

Over the last several months, I have become convinced that we as historians need to show our work more. When we are researching, writing, developing exhibits, conducting oral histories, and maintaining important archival documents, we are doing the work of history. Good history is a discipline, much like math. We were trained in graduate schools or through mentors in the field on how to research, write, develop a thesis, and how to create a finished product to share our findings with the public. The problem is we typically don’t reveal how we got there.

Over the last several months, I have become convinced that we as historians need to show our work more. When we are researching, writing, developing exhibits, conducting oral histories, and maintaining important archival documents, we are doing the work of history. Good history is a discipline, much like math. We were trained in graduate schools or through mentors in the field on how to research, write, develop a thesis, and how to create a finished product to share our findings with the public. The problem is we typically don’t reveal how we got there.

In 1998 in the seminal work The Presence of the Past, Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen reported that history museums were the most trusted place to get history information. Over the last few years, however, we have seen a new version of History Wars. Historians are accused of rewriting history, being unpatriotic, and being part of the decline of American civilization. President Donald Trump in his remarks during the White House Conference on American History said, “The left [mainly historians in the context of his speech] has warped, distorted, and defiled the American story with deceptions, falsehoods, and lies. There is no better example than the New York Times’ totally discredited 1619 Project. This project rewrites American history to teach our children that we were founded on the principle of oppression, not freedom.” What brought about this change where historians are viewed as Marxist and radical for sharing stories that look critically at America’s past?

My theory is that we need to show our work more. Most of my friends know I “do something with history” and want me to be on their trivia team because they think I know all the dates in history. They do not understand the work that goes into the research for an exhibit, the authenticating of an object, or the publishing of an article or book.

We need to find ways to pull back the curtain and show how the interpretation of history changes because of the dedicated work of historians.

Dr. Robert R. Weyeneth said in his 2014 address to the National Council on Public History, “My proposal is that we let the public in on this trade secret. One way to do this at museums and historic sites is to shine some light on the “interpretation” at the property. Visitors may not now the technical meaning of “interpretation” as applied to an historic site, but they are smart and curious—and many can be drawn into an explanation of why some subjects are discussed at the site, but not others. Why are certain questions asked and answered, but not others? Why do we hear the historical voices or outsider judgements that we do? Why are some pedagogic strategies employed rather than others? Shining light on the “interpretation” means saying: we cannot cover everything, choices have to be made, let us tell you how we made the choices we did.”

I recently visited three museums in Virginia that did just that—showed their work to the public. They are major institutions with large budgets, but what they did can be replicated in any history organization with little cost.

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello: While touring this site with my son, I started to notice a trend in the signage around the site. Each one had a box toward the lower right-hand corner that explained how the information shared on the sign was found. For example, an interpretive sign about Mulberry Row (where the enslaved people at Monticello lived and worked) included a statement under the heading “Learn More.” It said, “Monticello is on of the best-documented plantations in America. Our understanding of Mulberry Row is the product of more than 50 years of archaeological and historical study.” Visitors were then encouraged to download the site’s app to learn more. Other signs on Mulberry Row referenced specific historical documents such as census records, oral interviews, and Jefferson’s own notes to let visitors know that the interpretation was based on facts and research.

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello: While touring this site with my son, I started to notice a trend in the signage around the site. Each one had a box toward the lower right-hand corner that explained how the information shared on the sign was found. For example, an interpretive sign about Mulberry Row (where the enslaved people at Monticello lived and worked) included a statement under the heading “Learn More.” It said, “Monticello is on of the best-documented plantations in America. Our understanding of Mulberry Row is the product of more than 50 years of archaeological and historical study.” Visitors were then encouraged to download the site’s app to learn more. Other signs on Mulberry Row referenced specific historical documents such as census records, oral interviews, and Jefferson’s own notes to let visitors know that the interpretation was based on facts and research.

Colonial Williamsburg Art Museums: My favorite part of my recent visit to Colonial Williamsburg was their art museums. They had some wonderful exhibits, but the one that captured my attention the most was one exhibit case and panel about a chair called “Become the Detective.” It showed a wingback chair, but it was cut to show the layers added to the chair over time. They showed how the chair looked like a dumpster dive find at first. Then, they showed how the curator carefully went through each level of fabric and stuffing until they got to the original frame which proved to be a colonial treasure. Their exhibit showed photos of each stage of the process on a single exhibit frame which was very compelling. In other sections of the gallery, they also examined reading the evidence of historical artifacts and how touching can destroy items. This part of the exhibit was particularly effective as they had put sample materials (silk, steel, wood, leather, etc.) on display for a summer season asking visitors to touch a section of it while the other half remained covered in plexiglass. They then turned the results into an exhibit explaining why museums ask visitors not to touch certain objects. This exhibit showed the public how a curator researches and preserves decorative arts items.

Colonial Williamsburg Art Museums: My favorite part of my recent visit to Colonial Williamsburg was their art museums. They had some wonderful exhibits, but the one that captured my attention the most was one exhibit case and panel about a chair called “Become the Detective.” It showed a wingback chair, but it was cut to show the layers added to the chair over time. They showed how the chair looked like a dumpster dive find at first. Then, they showed how the curator carefully went through each level of fabric and stuffing until they got to the original frame which proved to be a colonial treasure. Their exhibit showed photos of each stage of the process on a single exhibit frame which was very compelling. In other sections of the gallery, they also examined reading the evidence of historical artifacts and how touching can destroy items. This part of the exhibit was particularly effective as they had put sample materials (silk, steel, wood, leather, etc.) on display for a summer season asking visitors to touch a section of it while the other half remained covered in plexiglass. They then turned the results into an exhibit explaining why museums ask visitors not to touch certain objects. This exhibit showed the public how a curator researches and preserves decorative arts items.

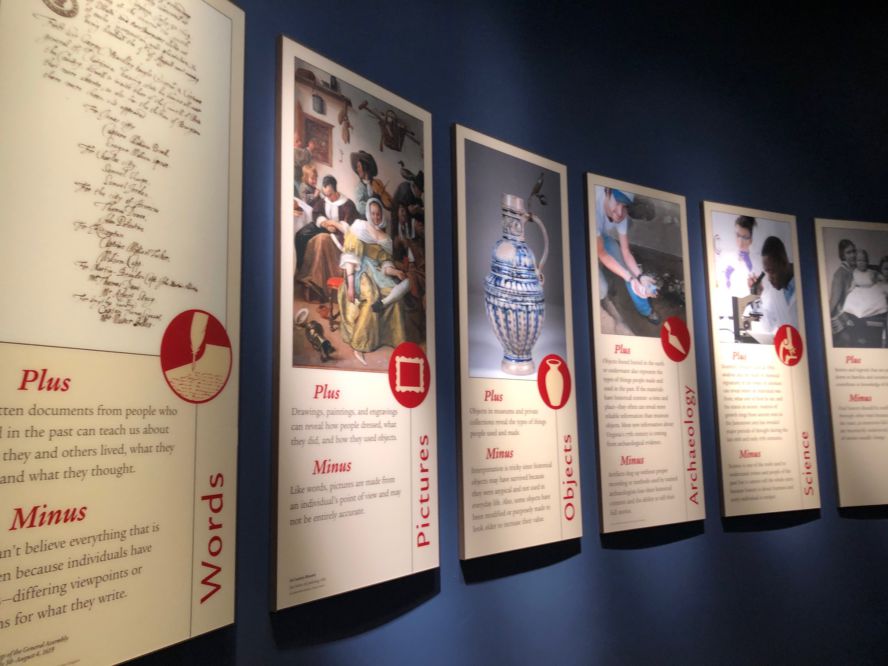

Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation: The museum at Jamestown was recently redone and is full of great visuals, artifacts, and interpretation. It also has an exhibit near the front called “How We Know What We Know.” The opening panel reads, “We research and interpret the past using evidence from six main sources: words, pictures, objects, archaeology, science, and oral history. There are pluses and minuses for each type of experience. Look for the icons telling you how we know what we know as you go through the galleries.” Following this introductory panel are additional panels featuring each of the six sources they cite as tools they use to interpret the past. They also highlight the pluses and minuses associated with each source. Throughout the rest of the museum, panels include icons related back to the source that provided the information for the text (i.e. a frame for pictures or a trowel for archaeology).

At this point, you may be thinking, that is great for them, but you don’t have their resources or space at your site. That may be true, but you can still show your work.

- Add exhibit labels that explain to visitors how you know what you know about the story or object. It can be done cheaply and easily and lets visitors see that your exhibit is based on sound research.

- Host curator talks. You probably do not have the ability to put on a full-scale exhibit like Colonial Williamsburg, but you can highlight the work of your curator in a different way. Film them explaining how they authenticated an object or reading an object and post on your website or social media. Instead of focusing on the final product of their research, spotlight the work itself.

- Offer behind-the-scenes tours of curatorial storage. As an AASLH staff member who used to run our onsite workshop program, I have had the privilege to go behind the scenes of dozens of history museums and it is always enlightening. You could offer a peek behind the curtain as a special tour (and charge for it) to show how you take care of the objects entrusted to your museum.

- Incorporate primary sources into your guided tours. Historic house museums often don’t have collections storage areas that can be opened to the public, but they do have the advantage of a live interpreter. As you are guiding visitors through the building, add information about how you know what you know. You can explain how a shadow in brick shows where a window was originally. You can also tell how census records, slave schedules and bills of sale, letters, family diaries, and other archival material helped you know what you know about the building and the people that lived and worked in it. I would suggest incorporating copies of the original documents so visitors can see the primary source that helped unlock a piece of your interpretation.

There are lots of other creative ways that can illustrate the discipline of history work to the public. As discussions around “Museums Are Not Neutral” and accusations of revisionism resonate in our field, we have a great opportunity to show the public the amount of work historians do before opening an exhibit, publishing a book or article, or offering a walking tour.

Unlike in The Wizard of Oz, pulling back the curtain on our field will not show us to be a humbug. It will show us to be people with a curiosity about the past who want to uncover new information to be able to tell the full history of America’s past, warts and all.

Bethany L. Hawkins is the Chief of Operations at the American Association for State and Local History. She can be reached at [email protected].