By Jason Hanson, Chief Creative Officer, History Colorado

The White House released a statement on August 21 entitled “President Trump is Right about the Smithsonian.” It is, presumably, a follow-up to the president’s social media post earlier that week claiming that museums are the “last remaining segment of ‘WOKE'” and the Smithsonian is “OUT OF CONTROL” and only focused on “how horrible our Country is, how bad Slavery was, and how unaccomplished the downtrodden have been” and that they (we) deserve the university treatment.

This is a bit of conjecture, though. The statement doesn’t pause to explain what it is referring to, specifically what the president is right about, before it launches into a bullet-pointed list of examples of the Smithsonian’s alleged shortcomings. A reader versed in rhetorical strategy might assume that the failure to define the argument is a tactic for making attacks easier to sustain and escalate.

Most of the media coverage and reaction from the museum field so far has focused on the power dynamics, namely whether the president can bend the independently governed but financially beholden Smithsonian to his view of American history. The broader museum field seems to be the next target of ideological intervention, following on the Trump administration’s playbook with universities and law firms. The rest of the reported reaction seems to focus on the chilling effect the administration’s assault may already be having on museums broadly. It’s been mostly vibes, anxiety, and pearl clutching, which is no way to engage in an argument.

But this critique deserves to be considered seriously. The administration is engaging on terms that museums and scholars should recognize: It has offered a critique and presented evidence intended to bolster that argument. Those of us in the museum field are used to looking at evidence and evaluating it. In fact, our sacred social contract is to present information rooted firmly in evidence to help our patrons make sense of their world and how we got to now. That is why museums have consistently ranked as the most trusted institutions in American life (far more trustworthy than the federal government, for what it’s worth). We can and should examine the evidence that has been offered. It’s what we do.

The President Might Be Right

Some of the evidence presented in support of the president’s rightness may be open to robust debate. What flags should be flown atop our national museums? Which pieces of art are worthy of exhibition on such prominent stages? How do we curate the stories, viewpoints, and people that are included in various exhibitions? These are all topics worthy of energetic consideration.

In most cases they have received exactly that, and what we see at the Smithsonian and other leading museums reflects the expertise, judgement, and best practices of trained museum professionals. But such conversations can and should be regularly revisited.

Some of the White House complaints have been already acknowledged as valid critiques. Most prominently, though it is the first example on the list, there’s no further debate about the controversial “White Culture” chart that seems to have first trained conservative sights on the Smithsonian. In the summer of 2020, after it was spotlighted by critics online, that chart was acknowledged as an error and quickly taken down by the National Museum of African American History and Culture at the direction of then-interim director Spencer Crew.

Nothing Muddles an Argument Like Flimsy Evidence

Many of the examples put forward in the White House statement are hardly convincing evidence of a nefarious groupthink conspiracy among museums. Instead, too many of these points of evidence come across as confusing, flimsy, insincere, or lazy.

In the confusing and flimsy camp, it’s hard to decode how acknowledging that some Latino people have disabilities, that some skaters identify as LGBTQ, that art can provoke conversations about power and identity, or that the Pilgrims who established the Plimoth Colony were colonizers are indictments of how “horrible our Country is.” Or that a stop motion pencil portrait of Anthony Fauci, which is reproduced in the memo, is celebratory or a political statement. Even Rasputin has portraits in museums, and better ones at that. It’s a fundamental misunderstanding of museums to presume that everything and everyone they present is an endorsement or a celebration.

Anthony Fauci by Hugo Crosthwaite (2022). Image from the National Portrait Gallery.

Additionally, it’s worth tracking back to the premise articulated in the president’s post that museums are too “woke” because some of our work illuminates “how bad slavery was.” That claim is confusing at best. It should go without saying, but slavery in America was, in the very most basic terms as we understand them today, “bad.” The enslavement of hundreds of thousands of people based solely on the color of their skin was also brutal, violent, and dehumanizing. And economically enriching or crippling in ways that persist to the present. And a betrayal of the ideals articulated in the Declaration of Independence that even its author, Thomas Jefferson, recognized and struggled with as he proclaimed first and foremost that all of us are created equal and have a natural right to life, liberty, and a chance to be happy.

If the evidence the White House is offering up in support of its argument stopped here, it might be nothing more than a muddled complaint. However, and more concerningly, the statement also offers up examples that are lazy or, worse, insincere. These are concerning because they may look, on their face, like legitimate evidence. And because the volume of supposed examples is part of the evidence. Maybe those who assembled the White House statement thought that no one would check them, or they themselves didn’t check them before pasting them into the list. But we in the museum field should, as we do, examine the evidence.

Disingenuous Evidence Raises Questions About Sincerity and Trustworthiness

In particular, two complaints about the National Museum of the American Latino caught my eye as an enlightening example of how disingenuous and clumsy some of these critiques are. They both relate to the nascent museum’s interpretation of the Mexican-American War, which the US and Mexico fought from 1846-48, and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that secured the peace in 1848.

They caught my eye because we know this history in Colorado. In fact, in 2023, I had my eye on the treaty literally when History Colorado was able to borrow original pages from the National Archives for inclusion in our Borderlands of Southern Colorado exhibition at the History Colorado Center in Denver. The land we call Southern Colorado today is a product of that war and the treaty that ended it, and we studied them carefully in crafting our own interpretation.

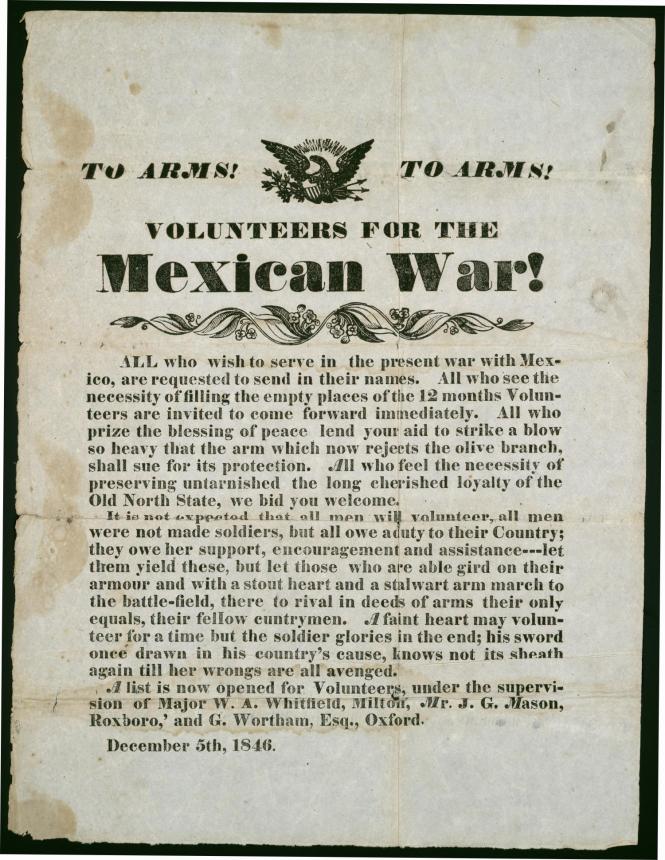

Posters like this did, in fact, open up divisive conversations among Americans in 1846 about whether the US should go to war with Mexico. Image displayed by the National Museum of the American Latino courtesy of Courtesy of University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History.

First, the White House statement says:

The National Museum of the American Latino… frames the Mexican-American War as “the North American invasion” that was “unprovoked and motivated by pro-slavery politicians.”

It cites a webpage with information about a printing press in the ¡Presente! exhibition, which is featured in the museum’s showcase gallery within the National Museum of American History while it undertakes the process of building its own museum. The criticism zeroes in on the caption for a recruiting poster calling volunteers “To Arms!” for the “Mexican War,” which the caption describes this way:

Posters like this were printed en masse across the United States to recruit the almost 75,000 men who volunteered to fight in the Mexican-American War (1846–1848)—known by Mexicans as the North American Invasion. US public opinion was divided over the war, with many considering it unprovoked and motivated to by pro-slavery politicians.

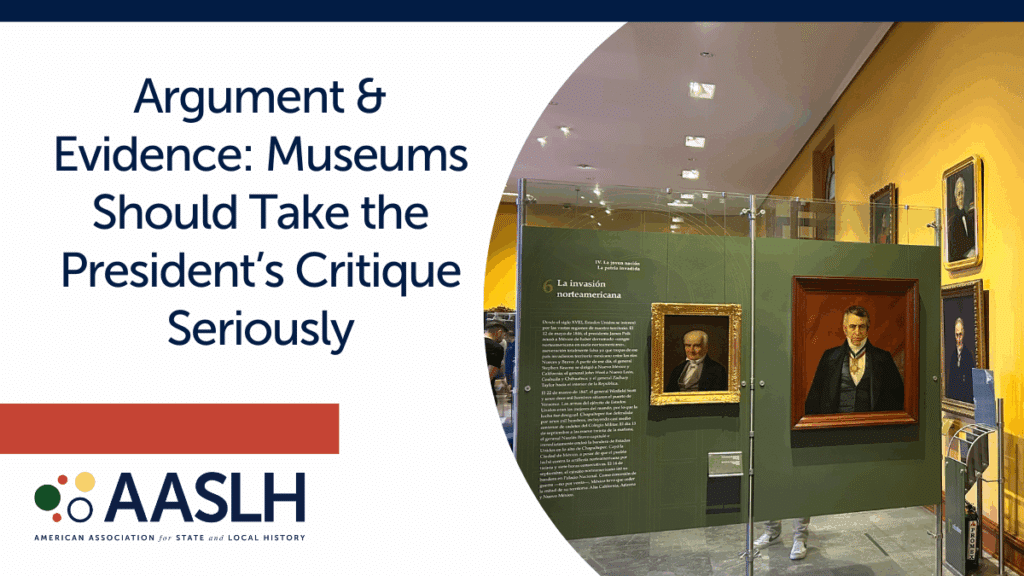

The museum is clear that it is describing how Mexicans characterized the war, unsurprisingly, as an invasion. Anyone who has recently visited the Castillo de Chapultapec in Mexico City, which is the national history museum (akin to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, DC) and also a castle that was the site of a key battle in the Mexican-American War, can confirm that this is how Mexicans characterize the war. Here is a photo of the section in the museum’s core exhibition that specifically addresses the war:

Castillo de Chapultapec’s presentation of the war with the United States. Photo by and courtesy of the author, June 2025.

If you zoom in you can see the primary interpretation there on the left: “La invasión norteamericana.” Translated into English, the title is “The North American Invasion.” It goes on to assert that President Polk’s claim that Mexico provoked war when it “shed American blood on American soil” was “aseveración totalmenta falsa” (“a totally false statement”) and that in fact US troops had “invadieron territorio mexicano” (“invaded Mexican territory”). Mexico’s official museum is unambiguous about characterizing the war as an invasion, which is in fact what the National Museum of the American Latino’s caption was relating.

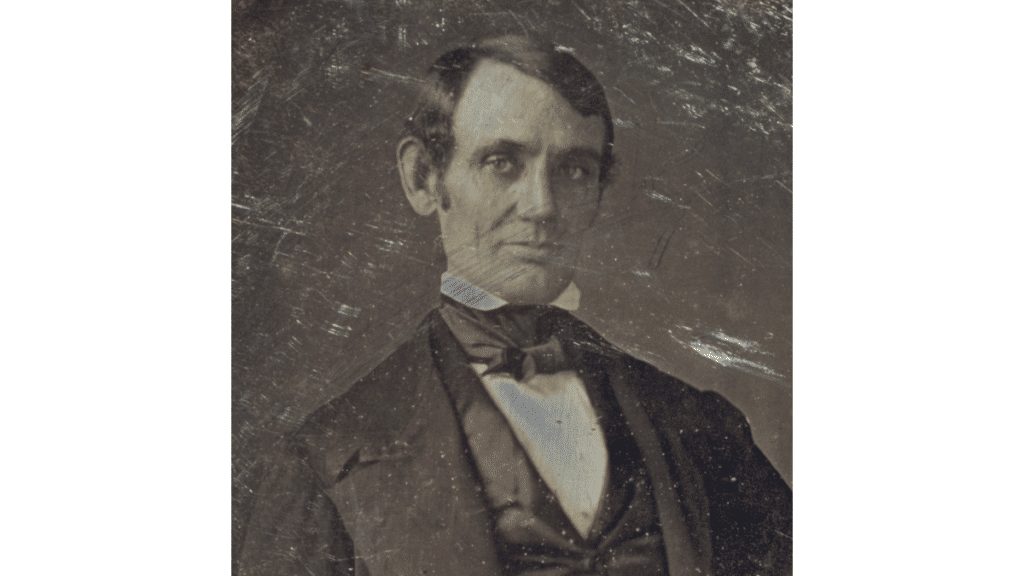

This isn’t just the opinion of modern Mexican historians. Abraham Lincoln was among those who, as the National Museum of the American Latino caption notes, considered the war unprovoked and a guise for expanding slavery. A representative from Illinois at the time, Lincoln was outspoken in accusing Polk of invading Mexico under false pretenses, with manifest destiny and expanding territory for slavery as his transparently ulterior motives. Lincoln introduced the “Spot Resolutions” in December 1847 as the war was ongoing in an attempt to expose those motives, and gave a rousing speech against the war and Polk in the House in January 1848 as treaty negotiations were underway. He spoke out even though it was politically unpopular in his home district—Democrats accused him of being unpatriotic, and for years after he was called “Spotty Lincoln” by his opponents.

Abraham Lincoln around the time he was vocally opposing US involvement in the Mexican-American War. Image courtesy of Library of Congress, https://lccn.loc.gov/2004664400.

The second suspect White House claim that caught my eye (and not just because of the garbled grammar) refers to the aftermath of that war:

The National Museum of the American Latino describes the post-Mexican-American War California describes [sic] a “Californio” family losing their land to American “squatters.”

This example also comes from the same ¡Presente! website, and refers specifically to the plot of a book entitled The Squatter and the Don (full text here from Project Gutenberg). The museum’s caption reads:

In this book, a wealthy Californio family struggles to hold on to their ranches after the Mexican-American War (1846–1848). It reflects the experiences of many elite Mexican landowners in California. During this time, new Anglo-American migrants, called squatters, started claiming lands belonging to Californios for themselves.

Published in 1885 under a pseudonym by Maria Amparo Ruiz de Burton, a member of a wealthy Californio Mexican family who married an American army officer after the war, the novel does indeed draw from the author’s personal experience of the war and its aftermath on California’s Mexican community (commonly known then and now as “Califonios”). The narrative shows how Mexicans living in the ceded territory experienced the treaty as a profound and disorienting disruption, as the “border crossed them” (another complaint confusingly cited in the White House statement) and, despite the treaty’s guarantees to respect their rights, they quickly began to experience the loss of their property and their culture.

In an illustrative exchange between the main character, Don Mariano Alamar, and George Mechlin, an East Coast lawyer who becomes his American son-in-law, George says “I thought that the rights of the Spanish people were protected by our treaty with Mexico.” The Don responds that while the treaty stipulated that a “spirit of peace and friendship… was to be the foundation of the relations between the conqueror and conquered,” it was not long before the “the trusted conquerors would, ‘In Congress Assembled,’ pass laws which were to be retroactive upon the defenceless, helpless, conquered people, in order to despoil them.” As he laments the ways in which the US devised legal pretexts to diminish his rights and dispossess him of his land, he concludes: “We have had no one to speak for us.”

Several decades later, Maria Amparo Ruiz de Burton spoke through her book for Californios like the Don. It was a group she clearly considered herself a part of as she fought to retain control of her family ranch near San Diego after her husband died of malaria contracted while stationed with the Army in Virginia. Although the White House statement casts it as evidence that the Smithsonian is pursuing an anti-American agenda, it’s hard to see anything devious in noting the existence of this historical document that helps illuminate the views of some Hispanic people in California in the late nineteenth century. It’s hard to see it as anything but disingenuous.

Museums Know What Strong Evidence Looks Like

These are just some of the examples—many of them clumsy, confused, or disingenuous—put forward from the White House as evidence of the Smithsonian museums’ anti-American bias. If we were to go point by point through the statement, I think we’d be able to repeat this exercise. Which is exactly how professionals at leading museums would robustly analyze language and source material as a normal step in the development of exhibitions and educational materials rooted in the evidence.

Museum professionals know what strong evidence looks like. It is the foundation we stand upon as we make decisions about the best ways to empower our patrons with the scientific insights that help us discover the world around us, the art that encourages us to see that world through new perspectives, and the history that helps us make sense of how we got to now and who we are as Americans. And, in cases where the evidence does not hold up to scrutiny, we in the museum field know that we are better off not presenting it, no matter what agenda it aligns with. To do otherwise would be to risk our reputations as some of the most trusted institutions in America.

This essay was originally published in The Colorado Magazine. The views expressed on the AASLH blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of AASLH or its members.