Kids have a knack for asking legitimate questions. One of the most common is, “Why do we need to learn this history stuff?”

Kids have a knack for asking legitimate questions. One of the most common is, “Why do we need to learn this history stuff?”

Whenever I took college-level history courses, the professors on the first day of class told us, “Forget that garbage you learned in high school. Now you’re going to learn what really happened.”

A substantial number of library and museum visitors didn’t benefit from attending college, yet they still pay taxes supporting cultural institutions. Studies have shown that museums are one of the most trusted sources of information. They try to be havens of sanity and objectivity when discussing historical precedents, so why should budget cuts jeopardize their future? Remember, the future of you and your museum may depend on whether or not voters think your work is valuable and relevant.

Perhaps some of this predicament is caused by how the public perceives the role of history in a culture. People of all ages are hungry for their history, especially when they believe they’re getting the real deal. If that’s the case, then why continue accepting “feel-good” nonsense in classrooms, textbooks, and children’s media programming? Recent controversies about “slave quilts” and about black Confederate soldiers are just two examples. It’s dishonest and reprehensible to promote nostalgia for an idealized or imaginary past.

For too long, Americans saw history as a mass of disconnected factoids promoting a selective, convenient, and self-congratulatory nationalism. The history curriculum had students memorize dates and the feats of dead WASP males. But how can we as a nation expect our children to become active and engaged citizens if we only present them with, and test them on, this material? An electorate can’t make informed decisions about their candidates if self-serving politicians, media “entertainers,” and corporate textbook publishers espouse outright historical inaccuracies.

Part of the problem arises when we see historiography as static or carved in stone. It may help if we encourage people to see history as a dynamic, self-correcting process reflecting human complexity. There’s nothing wrong with revising our understanding; that’s what historians do. As new information comes to light, a responsible citizenry questions and re-interprets what it knows; the body politic, in turn, can revise its stories and re-chart its course.

So what are we supposed to learn from the “history experience?” It may help if we examine and define the process itself. The museum community is moving along a promising path by advocating the notion of sustainability. But sustainability isn’t a goal in itself; it’s part of the overall historical process of learning about connections and contexts. A sustainable approach toward history encompasses three things:

- Understanding the reasons why things are the way they are, be they our landscapes, our homes, our works, our associations and decision-making within the human community….or anything else;

- Learning how to tell the difference between the “history” and the “hooey,” by encouraging people to ask, “How do I know what I know is true?”; and

- Appreciating (not necessarily liking) the role of change in our lives, regardless of whether the changes are geological, cultural, linguistic, economic, architectural, or psychological. Change occurs at different rates. While not always for the best, it’s natural and inevitable. Change can be both destructive and invigorating, but we can’t look at change as the polar opposite of preservation or conservation. No, confronting change should spur us into action.

Information is available to us today on an unprecedented scale, but instant accessibility doesn’t automatically guarantee learning, let alone wisdom. We need tools of judgment to weigh, sift and measure the information flooding our brains. “Doing history” – of asking questions and of showing connections and contexts – hones those skills in ways that other disciplines do not.

That’s why Clio, the Greek muse of history, needs to sit on everyone’s shoulders.

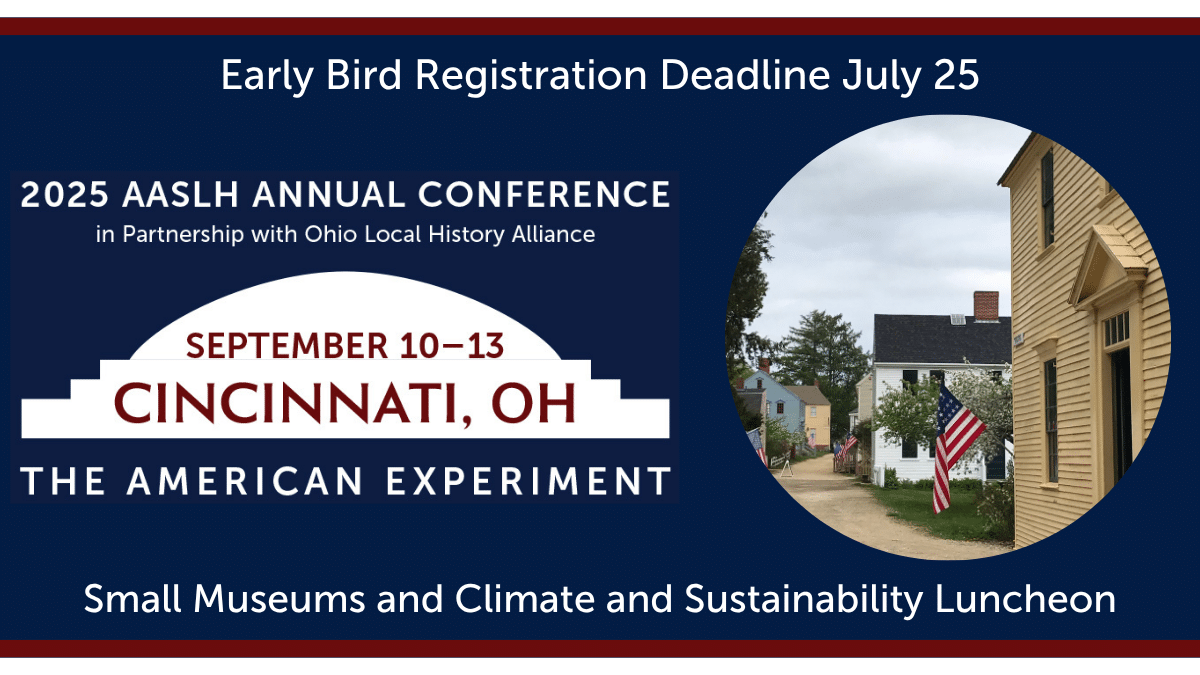

Bruce Teeple is a freelance writer, editor, local historian, speaker, gardener, wine maker, chicken farmer, and columnist for the Centre Daily Times in State College. Pennsylvania. A graduate of Penn State in history and political science, he served for nineteen years as curator of the Aaronsburg Historical Museum before joining AASLH’s Small Museums Committee. He is currently researching and writing As Good as a Handshake: the Farringtons and the Political Culture of Moonshine in Central Pennsylvania. His latest work is “Slavery In Post-Abolition Pennsylvania….And How They Got Away With It.”