Photos of Sami people and others dressed as Sami at the Nordic Museum.

By Benjamin Filene, North Carolina Museum of History, Raleigh, NC

Sometimes being on unfamiliar ground leads to new perspectives on one’s home turf. Through a Fulbright fellowship, I spent this winter and spring exploring the public history scene in Finland. Toward the end, I was invited to Bergen, Norway, to give a keynote for the annual meeting of the Nordic Association for American Studies, whose conference theme was “Monuments.” I titled my talk “Etched in Stone vs. a Fluid Past: Monuments, Museums, and History-Making in Public.” My point that was that the Confederate monument wars in America have not only surfaced lurking racism but have shown that we history professionals have failed to convey to the public how history really works: that history-making is an act of interpretation and assembly—that these statues are not eternal statements, but historically contingent ones tied to power. How, I asked, can historians “pull back the curtain” and reveal the process of history-making in action? I shared some thoughts about how we might do so in scholarship, in the classroom, and in museums. But at the time, I worried it might all sound too theoretical or idealistic. Then I went on to Stockholm and saw striking examples of what I had in mind in three different museums!

Of the three, the Swedish History Museum most directly explores how museums construct the past. Its exhibition History Unfolds introduces the museum itself as a “Reality Machine,” one that creates history and reflects contemporary ideas of identity and power.

The exhibition then offers visitors tools and case studies for thinking about how that process of reality-formation works. For instance, it displays a helmet from 600 C.E. When the helmet was unearthed in the nineteenth century, its elongated form was used to bolster a theory of the racial distinctiveness of the Swedes. Then in 1915, the exhibition notes, artist Carl Larrson incorporated these helmets into a painting showing the sacrifice of a Swedish king at a mythical “heathen temple.” Larsson felt that the helmets “make us believe in the original nobility and greatness of our race.”

Larsson’s painting contributed to a national origin myth, one that entered the museum itself. In the 1970s or ‘80s, History Unfolds tells us, the Swedish Museum created a model to depict the “heathen temple” in an exhibition at the museum. Curators recently found it in storage and put it on display again—this time to illustrate the museum’s complicity in mythmaking.

Detail from Carl Larsson’s “Midwinter Sacrifice.” The exhibition’s caption reads “An Artist’s Construction of a Nation.”

With this one neat example, History Unfolds has shown how the same artifacts can carry very different meanings in different times, shifting as historians gain knowledge, bring new frames of reference, and ask different questions. The museum’s tagline on its website nicely signals the contingency of the historical constructions that the museum as “reality machine” produces: “Based on True Stories.”

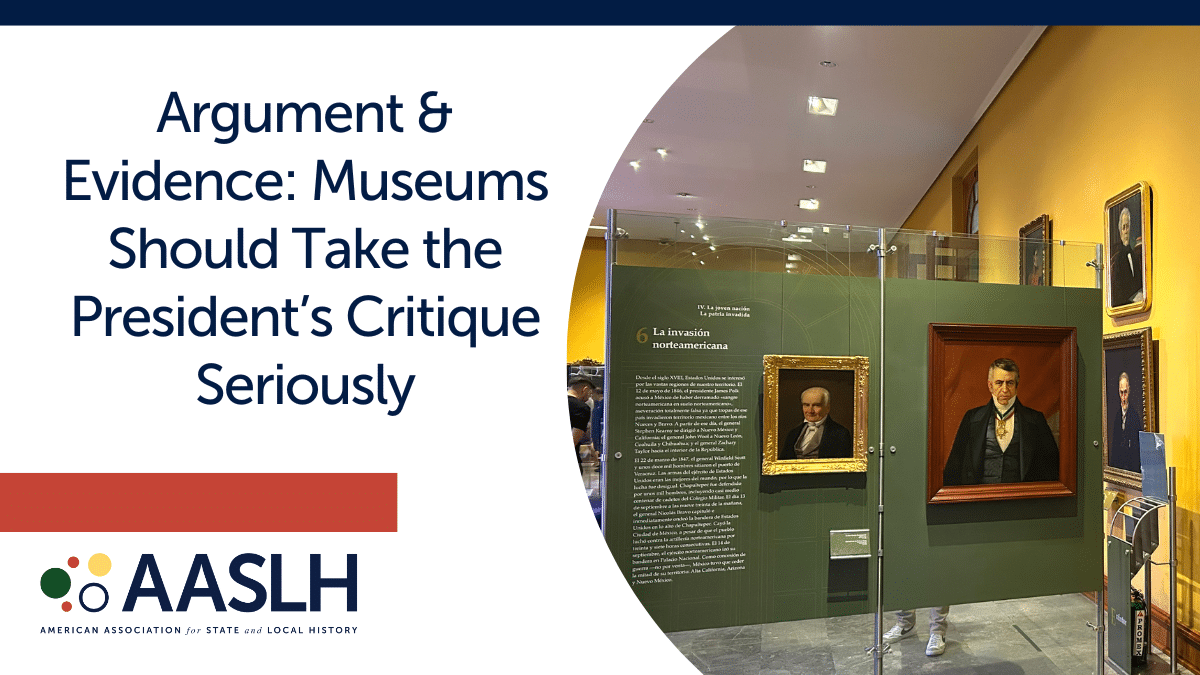

Across town, the Nordic Museum addresses the power of history-making in an exhibition on the Sami, the indigenous people of the Nordic region. The mistreatment of the Sami, the exhibition shows, is not only a question of land rights and economic hardship but also of representation. In the latter, the museum itself has played an uneasy role, one that it now seeks to address directly. The exhibition begins with a series of big questions about storytelling and perspective: “Who is Swedish?” “Whose history?” “Whose eyes?” “Whose voice?”

Then, by example, it teaches us how to see historical evidence in new ways. Who is a poser in these photographs (see first blog image)? The accompanying text resists easy answers.

The exhibition extends the lesson about the slipperiness of identity into the present day. It invites visitors to listen to excerpts from interviews with some members of its advisory committee, and asks us to consider, “Is that…Sami?” Throughout, the museum is not just a reporter but an actor in this story of representation and power.

A long thin display case runs through the center of the gallery. It holds the museum’s catalogue records for Sami-related objects. Visitors can flip through the entries, see what the museum owns, and consider how, why, and to what end. These cards don’t come with labels; the museum resists the temptation to have the last word.

A long thin display case runs through the center of the gallery. It holds the museum’s catalogue records for Sami-related objects. Visitors can flip through the entries, see what the museum owns, and consider how, why, and to what end. These cards don’t come with labels; the museum resists the temptation to have the last word.

In my final Stockholm encounter, the Vasa Museum took the approach to history-making that may carry the most weight with visitors—not just talking about it at a meta level but experimenting right before our eyes. The museum is built around a massive reconstruction of a seventeenth-century shipwreck, a boat that sank in the Stockholm harbor in 1628 almost immediately after it was launched, in front of hundreds of residents who had come to see it off on its maiden voyage.

Vasa’s latest exhibition asks a new question: Where are the women in this story? Traditionally, the exhibition tells us, they have been absent. It was easy to say that they rarely traveled on these kinds of boats or that, anyway, sources don’t exist to document their lives. The museum now rejects both of those assertions, and takes the opportunity to explain to visitors why:

Seventeenth-century society depended heavily on the work and presence of women. The image of women in history is strongly influenced by the historical vision of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. That is why research on women less commonly reaches the public. Popular history, the media, and textbooks have seen women’s history as something to one side of “real” history.

In short, the text concludes, “The lack of focus on women’s history has been a greater problem than a lack of sources.” “Always Present—Often Invisible,” reads the exhibition’s subtitle, and Vasa’s Women sets out to rectify that invisibility. It analyzes the clothing and jewelry found on the two female bodies recovered in the excavation for insight into their class position. It examines the teeth and bones of their skeletons for clues to their nutrition and signs of injuries. It interprets court records and diaries. It shows video interviews with passionate archaeologists and women’s historians.

One vitrine prominently features an absence. A small case shows handles made from antler. The handles were recovered from the sunken ship, but the leather bag that they would have held is long gone. Instead of shelving the handles, the museum here displays them along with an image of what the bag might have looked like, and it offers a metaphor: “Working with bone and antler was seen as a male craft, while leatherwork was seen as a female craft. Therefore, the handles could perhaps symbolize the presence of males and the absence of females in the writing of history. However, this does not mean that women were invisible or unimportant in the 17th century.”

By looking with new eyes at old evidence, the women of Vasa begin to come into focus, as this graphic suggests:

The museum itself appears astonished and invigorated by the process it has gone through—”we see the whole of the 17th century more clearly”—and it pledges to put its new lenses to work in other places, too: “In the coming years, the Vasa Museum will be revising and renewing its exhibitions. From our own collections and sources we will look for new narratives and perspectives….”

The work of history, in other words, is an ongoing creative act. By acknowledging that historians don’t have all the answers and by allowing visitors to see the process of knowledge-creation in motion, these museums are building institutional trust. They are also opening doors to conversations whose importance extends far beyond the gallery walls: about what constitutes a shared past, about who gets to tell that story, and about when—and when not—to etch that story in stone.

Benjamin Filene is Chief Curator at the North Carolina Museum of History and can be reached at [email protected]. For additional blog reports from his time in Finland, see https://bfilene.wixsite.com/website/home.